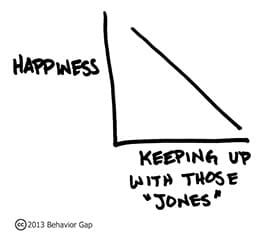

Happiness is getting get off the ‘positional treadmill’

Mickey Kim / May 17, 2019

You know what’s worse than judging a book by its cover? Judging a book by its cover…AND THEN making financial decisions based on what you guess the book might tell you. And yet, we do this all the time. Not with books, but with people.

So says my friend, Carl Richards, founder of behaviorgap.com, his website that offers “simple sketches and a few hand-crafted words about money, creativity, happiness and health.” Carl is a Certified Financial Planner with a knack for using cocktail napkin sketches and a few words to explain financial concepts.

In 1949, Harvard professor James Duesenberry created the “Relative Income Hypothesis,” which says the utility we derive from consumption depends on what we consume and how much we consume relative to others. Because of this, we believe and act as if both what and how much we consume indicates where we stand in the societal pecking order. According to Richards, people tend to spend more “because the higher spending of others kindles aspirations they find difficult to meet.”

In classical economics, individuals are highly intelligent, perfectly rational and capable of unemotionally analyzing all relevant data. They possess tremendous self-control, enabling them to make optimal decisions, unburdened by biases. Picture Mr. Spock.

In reality, Homo Economicus is a mythical character existing only in theory. Not only are humans highly emotional and lacking in self-control, they are influenced by all sorts of biases. They act on biases in irrational and predictable ways, often leading to poor decisions. In fact, we’re more like Homer Simpson.

Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business was a pioneer in the field of behavioral economics, the study of how psychology and economics intersect. He won the Nobel prize in economics in 2017 because “by exploring the consequences of limited rationality, social preferences and lack of self-control, he has shown how these human traits systematically affect individual decisions as well as market outcomes.”

Your neighbor rolls up in a brand new Ferrari. According to Richards, not only do you make a subconscious judgement about your neighbor based on the car she is driving, you become more likely to spend more on your ride just to keep up with her.

Why? As Homer Simpsons, we create stories that fit the “facts.” In this case:

1. Because she’s in it, she bought it (Appearances = Spending)

2. Because she bought it, she’s rich (Spending = Net Worth)

3. Because she’s rich, she’s happy (Net Worth = Happiness)

As Richards points out, this story is a “house of cards, layer upon layer of assumptions that have no basis in reality.” Your neighbor may have borrowed the car from her sister. Even if she bought it, maybe owning a Ferrari was her lifetime goal and she has $0 saved for retirement. Even if she’s rich, do you know any miserable rich people? We just don’t know.

Similarly, if your employer offered to double your salary, would you jump at the chance? Of course you would! However, you’ll probably be surprised to learn this “no brainer” decision depends on whether someone else is involved.

Classical economists assume “utility” is a function of an individual’s “endowment.” In other words, more of a good is better, independent of the individual’s relative position. However, a 1995 survey of faculty, students and staff at the Harvard School of Public Health showed people do not act independently of relative position, which can have a powerful and dangerous behavioral influence.

The survey consisted of twelve questions, each containing two states of the world. In each state, respondents were told how much of a good they had and how much others had.

Amounts of good were structured so that in the “positional” state, the respondent had more of the good than others. In the “absolute” state, amounts of the good for both the respondent and others were greater than in the positional state, but respondents had less of the good than others.

Researchers asked respondents which of two worlds they would prefer to live in: State A (“Positional”), earning $50,000 per year while others earn $25,000 or State B (“Absolute”), earning $100,000 per year while others earn $200,000. Unbelievably, about half of the respondents preferred earning 50% less, as long as their relative position was high.

The challenge of being on this “positional treadmill” is the goal-line is always moving. Basing our feeling of self-worth and spending on stories we tell ourselves is just plain crazy.

The opinions expressed in these articles are those of the author as of the date the article was published. These opinions have not been updated or supplemented and may not reflect the author’s views today. The information provided in these articles does not provide information reasonably sufficient upon which to base an investment decision and should not be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular stock or other investment.

Subscribe

Subscribe to stay up to date with the latest news, articles and newsletters from Kirr Marbach.